After having completed the part one and its first exercises, I feel the need to sum up briefly the major learning points.

Part one explored the variety of relationships between the photographer and the subject.

The most important division is the one adopted here, between when people are aware that the photographer is taking their picture and unaware.

The practical work in this course is as much about social relationship as photography.

Over the years, the "classic" portrait composition has come to be a framing that includes the torso, head and shoulders.

If the shoulders are too square to the camera then the photograph may look static and formal, too much like an identity photo.

The tilt of the subject's head also make a difference.

The background should be relatively unobtrusive unless it has a constructive role to play in the photograph.

There are times when it makes sense to bring the location into the photograph and even to let it play a leading role.

A short checklist for a setting

• Is it reasonably consistent in tone and features?

• Does it complement or contrast with the person? Either can work.

• Does it need tidying and/or cleaning? Look for scraps on the floor, anything obviously disordered, drawers left open, doors ajar, and so on.

• Are there unnecessarily distracting objects in view? Look for strong clashing colours, images (posters, photographs, paintings) and/or words (posters, book covers, signs). Do they add or detract?

Concerning light, beware of using on-camera flash; this has its uses, but used as the sole illumination is rarely flattering or acceptable for portraits.

There is, therefore, a big difference in effect between sunlight and shade.

On the plus side, sunlight has sparkle, good contrast and can produce catchlights in the eyes; against this, it can appear harsh, cast unattractive shadows across the face, and cause squinting.

In favour of shade, there are no shadow problems and the overall effect is soft, which is good for downplaying skin blemishes; against this, there may be no modelling effect, so that the effect is flat and the face lacks volume.

There is often value in encouraging subjects to occupy themselves in some simple way.

This usually involves your subject holding something or demonstrating how something is done, and neither of these needs to be complicated.

One of the standard variants is the interview shot, a staple of magazine and newspaper feature pages.

One highly effective way of making a portrait, although it takes some preparation, is to set the person in the context of what they do – whether work, an interest, some characteristic location or unique activity.

In this sense it is a form of photo-journalism.

This kind of portrait lends itself to a natural, artless approach, and by encouraging the subject to do whatever comes naturally, you have the strong possibility of capturing an unselfconscious spontaneity.

Facial expression is arguably the single most important variable in a portrait.

Establishing a rapport with the subject begins from the instant of the first have contact.

If the person is a friend or relative then existing relationship will play a role.

Otherwise, it will probably need to establish a relationship that inspires trust.

A checklist for reviewing a portrait sequence

• Is the general composition satisfactory?

• Is there anything behind the subject that appears to emerge from the head?

• Is there anything that can be left out of the frame to make it simpler?

• Is the lighting balance about right?

• How is the angle of the head?

• How is the facial expression?

• Does the body language communicate ease, tension, alertness, or what?

Sunday, April 20, 2014

Saturday, April 19, 2014

Exhibition - "Paparazzi! Photographers, stars and artists"

Centre Pompidou-Metz dedicates a very well prepared exhibition to the phenomenon and aesthetic of paparazzi photography through more than 600 works (photography, painting, video, sculpture, installation, etc.).

Covering fifty years of celebrities caught in the lens, "Paparazzi! Photographers, stars and artists" considers the paparazzo at work by examining the complex and fascinating ties that form between photographer and photographed, going on to reveal the paparazzi influence on fashion photography.

By associating some of the genre's leading names, including Ron Galella, Pascal Rostain, Bruno Mouron, Tazio Secchiaroli, with reflections on this modern-day myth by Richard Avedon, Raymond Depardon, William Klein, Gerhard Richter, Cindy Sherman and Andy Warhol, "Paparazzi! Photographers, stars and artists" sets out to define the paparazzi aesthetic.

The exhibition is divided into five parts: Introduction, Photographers, Stars, Artists and Conclusion

1. RED CARPET (INTRODUCTION)

The visitor steps into the exhibition space to be immediately confronted with paparazzi flashes from an installation by Malachi Farrell, titled Interview (Paparazzi).

Photographs showing a pack of paparazzi "hunting their prey" create a mise en abyme that plunges the visitor into a new role as a star, while giving them a taste of the pressure celebrities are under.

2. PHOTOGRAPHERS

The profession of paparazzo is more complex than it seems.

Paparazzi must be ingenious, mounting what are often delicate, high-risk operations. They each have their tricks of the trade and tales to tell which together form the grand story of "paparazzism".

In a series of interviews with paparazzi, a presentation of their tools (including spy cameras, long lenses and disguises), photographs by Francis Apesteguy, Olivier Mirguet, Jessica Dimmock and Christophe Beauregard, and an excerpt from Raymond Depardon's Reporters film, this section goes behind-the-scenes of the paparazzi.

The figure of the paparazzo was invented by Federico Fellini in 1960.

The name is a contraction of "pappataci" (mosquitoes) and "ragazzi" (boys).

The paparazzo is portrayed as a post-modern anti-hero.

Since La Dolce Vita, he has become one of the mythical figures of popular culture.

Excerpts from films by Dario Argento, Federico Fellini, Brian De Palma, Louis Malle and Andrzej Zulawski, from the 1930s to the present, reveal the public's perception of the paparazzo as a solitary figure, often down on his luck.

Devoid of morals or scruples, and therefore hard to love, he is the double negative of the war correspondent.

3. STARS

Paparazzo is a male-dominated profession.

Its targets, on the other hand, are almost always epitomes of womanhood.

This section considers the case of eight women – Brigitte Bardot, Paris Hilton, Jackie Kennedy-Onassis, Stéphanie de Monaco, Britney Spears, Diana Spencer and Elizabeth Taylor – to show how the style and stakes of paparazzi photography have changed over half a century.

Celebrities are not just helpless victims.

When they spot the paparazzi, they can choose to play along with them and allow themselves to be photographed or not, in which case their reactions can range from a polite refusal to physical aggression.

They can also be a willing accomplice, going as far as to invent their own way of escaping the star system and its constraints.

This section presents celebrities' different reactions to the camera through a series of shots by the twentieth century's greatest paparazzi – Daniel Angeli, Francis Apesteguy, Ron Galella, Marcello Geppetti, Bruno Mouron and Pascal Rostain, Erich Salomon, Tazio Secchiaroli, Sébastien Valiela and Weegee.

4. ARTISTS

The paparazzi photo has a recognisable aesthetic, a result of the conditions in which it is taken.

These are on-the-spot, improvised images, with all the consequences this has on their composition: the long lens for distance shots, or the flash for close-ups, flatten the image.

Celebrities shielding themselves behind their hand has become the symbol of media aggression.

Since the 1960s, the paparazzi aesthetic has inspired numerous artists in Pop Art, post-Modernism and more contemporary movements, from Richard Hamilton to Paul McCarthy, including Valerio Adami, Barbara Probst or Gerhard Richter.

Fascinated by the image hunters’ approach, numerous artists and fashion photographers since the 1960s have stepped into their shoes for one or other project.

Photographers such as Richard Avedon, William Klein and Terry Richardson were first to get under the paparazzo's skin for a series of shots.

Many artists, including the American Gary Lee Boas, English artist Alison Jackson, and G.R.A.M., an Austrian collective, have also collected stars in the same way paparazzi do.

Since the 1980s, women artists such as Malin Arnesson, Kathrin Günter and Cindy Sherman have questioned the artist's celebrity status.

Celebrity magazines satisfy the demand of a media industry which has its own rhetoric and its own, unmistakable page layout.

Through works by Jonathan Horowitz, Armin Linke, Paul McCarthy and Andy Warhol, this last section raises the question of how paparazzi photos reach their audience.

Covering fifty years of celebrities caught in the lens, "Paparazzi! Photographers, stars and artists" considers the paparazzo at work by examining the complex and fascinating ties that form between photographer and photographed, going on to reveal the paparazzi influence on fashion photography.

By associating some of the genre's leading names, including Ron Galella, Pascal Rostain, Bruno Mouron, Tazio Secchiaroli, with reflections on this modern-day myth by Richard Avedon, Raymond Depardon, William Klein, Gerhard Richter, Cindy Sherman and Andy Warhol, "Paparazzi! Photographers, stars and artists" sets out to define the paparazzi aesthetic.

The exhibition is divided into five parts: Introduction, Photographers, Stars, Artists and Conclusion

1. RED CARPET (INTRODUCTION)

The visitor steps into the exhibition space to be immediately confronted with paparazzi flashes from an installation by Malachi Farrell, titled Interview (Paparazzi).

Photographs showing a pack of paparazzi "hunting their prey" create a mise en abyme that plunges the visitor into a new role as a star, while giving them a taste of the pressure celebrities are under.

Malachi Farrell - Interview

2. PHOTOGRAPHERS

The profession of paparazzo is more complex than it seems.

Paparazzi must be ingenious, mounting what are often delicate, high-risk operations. They each have their tricks of the trade and tales to tell which together form the grand story of "paparazzism".

In a series of interviews with paparazzi, a presentation of their tools (including spy cameras, long lenses and disguises), photographs by Francis Apesteguy, Olivier Mirguet, Jessica Dimmock and Christophe Beauregard, and an excerpt from Raymond Depardon's Reporters film, this section goes behind-the-scenes of the paparazzi.

Francis Apesteguy - Serge Gainsbourg

The figure of the paparazzo was invented by Federico Fellini in 1960.

The name is a contraction of "pappataci" (mosquitoes) and "ragazzi" (boys).

The paparazzo is portrayed as a post-modern anti-hero.

Since La Dolce Vita, he has become one of the mythical figures of popular culture.

Excerpts from films by Dario Argento, Federico Fellini, Brian De Palma, Louis Malle and Andrzej Zulawski, from the 1930s to the present, reveal the public's perception of the paparazzo as a solitary figure, often down on his luck.

Devoid of morals or scruples, and therefore hard to love, he is the double negative of the war correspondent.

3. STARS

Paparazzo is a male-dominated profession.

Its targets, on the other hand, are almost always epitomes of womanhood.

This section considers the case of eight women – Brigitte Bardot, Paris Hilton, Jackie Kennedy-Onassis, Stéphanie de Monaco, Britney Spears, Diana Spencer and Elizabeth Taylor – to show how the style and stakes of paparazzi photography have changed over half a century.

Ron Galella - Jackie Kennedy-Onassis and her husband

Celebrities are not just helpless victims.

When they spot the paparazzi, they can choose to play along with them and allow themselves to be photographed or not, in which case their reactions can range from a polite refusal to physical aggression.

They can also be a willing accomplice, going as far as to invent their own way of escaping the star system and its constraints.

This section presents celebrities' different reactions to the camera through a series of shots by the twentieth century's greatest paparazzi – Daniel Angeli, Francis Apesteguy, Ron Galella, Marcello Geppetti, Bruno Mouron and Pascal Rostain, Erich Salomon, Tazio Secchiaroli, Sébastien Valiela and Weegee.

Paul Schmulbach - Ron Galella and Marlon Brando, 1974

4. ARTISTS

The paparazzi photo has a recognisable aesthetic, a result of the conditions in which it is taken.

These are on-the-spot, improvised images, with all the consequences this has on their composition: the long lens for distance shots, or the flash for close-ups, flatten the image.

Celebrities shielding themselves behind their hand has become the symbol of media aggression.

Since the 1960s, the paparazzi aesthetic has inspired numerous artists in Pop Art, post-Modernism and more contemporary movements, from Richard Hamilton to Paul McCarthy, including Valerio Adami, Barbara Probst or Gerhard Richter.

Barbara Probst - Stills Gallery

Fascinated by the image hunters’ approach, numerous artists and fashion photographers since the 1960s have stepped into their shoes for one or other project.

Photographers such as Richard Avedon, William Klein and Terry Richardson were first to get under the paparazzo's skin for a series of shots.

Many artists, including the American Gary Lee Boas, English artist Alison Jackson, and G.R.A.M., an Austrian collective, have also collected stars in the same way paparazzi do.

Since the 1980s, women artists such as Malin Arnesson, Kathrin Günter and Cindy Sherman have questioned the artist's celebrity status.

Alison Jackson - The Queen

5. NEWSSTAND (CONCLUSION)

Celebrity magazines satisfy the demand of a media industry which has its own rhetoric and its own, unmistakable page layout.

Through works by Jonathan Horowitz, Armin Linke, Paul McCarthy and Andy Warhol, this last section raises the question of how paparazzi photos reach their audience.

Jean Pigozzi - Mick Jagger and Arnold Schwarzenegger, Hôtel du Cap, Antibes, 1990

Friday, April 18, 2014

"The Photograph as Contemporary Art" - Chapter 1: If This Is Art - Learning points

The course material includes also "The Photograph as Contemporary Art", a very interesting book written by Charlotte Cotton published by Thames and Hudson (London 2014 Third edition). As I decided to do for my practical course, I would like to keep track of my learning points as I gradually go on reading the book reporting the most important sentences by the above author.

No copyright infringement intended - photographs will be removed immediately upon request.

All the photographs in this chapter evolve from a strategy or happening orchestrated by the photographers for the sole purpose of creating an image.

The central artistic act is one of directing an event specially for the camera.

The roots of such an approach lie in the conceptual art of the mid-1960s and 1970s.

The act depicted in the photograph is what is artistically important.

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp, the father of conceptual art, submitted a factory-made urinal to the Armory Show in New York on the basis that art could be anything the artist designated it to be.

Today, only photographs remain of the original "Fountain", taken by Alfred Stieglitz.

In Mona Hatoum's "Van Gogh's Back" we jump mentally from the swirls of hair on the men's wet back to the starry skies of Van Gogh's swirling paintwork.

The enjoyment of such a photograph is based on our shift from registering a photographic image as a three-dimensional scene and that of a two-dimensional, graphic representation of the swirls of wet hair that we connect, via Van Gogh, to a patterned sky.

The American photographer and poet Tim Davis's series "Retail" depicts the darkened windows of American suburban houses at night, with windows reflecting the neon signs from fast-food joints.

The photographs reveal a subliminal imposition of contemporary consumer culture onto domestic life.

With the repetition of this night time phenomenon express his theory of the contamination of our privacy and consciousness by commercialism.

No copyright infringement intended - photographs will be removed immediately upon request.

All the photographs in this chapter evolve from a strategy or happening orchestrated by the photographers for the sole purpose of creating an image.

The central artistic act is one of directing an event specially for the camera.

The roots of such an approach lie in the conceptual art of the mid-1960s and 1970s.

The act depicted in the photograph is what is artistically important.

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp, the father of conceptual art, submitted a factory-made urinal to the Armory Show in New York on the basis that art could be anything the artist designated it to be.

Today, only photographs remain of the original "Fountain", taken by Alfred Stieglitz.

Alfred Stieglitz - Fountain by Marcel Duchamp, 1917

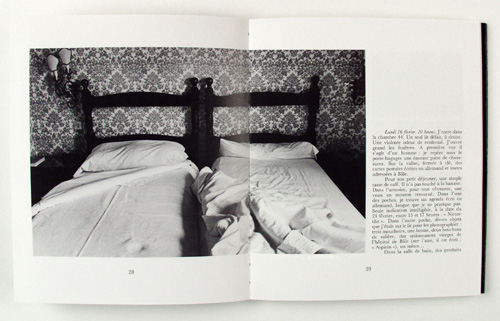

French artist Sophie Calle's art works conflate fact and fiction, exhibitionism and voyeurism, and performance ans spectatorship.

For her work "The Hotel" Calle took a job as a chambermaid in Venice and during her daily cleaning of the bedrooms, she photographed the personal items of their temporary inhabitants, discovering and imagining who they might be.

Sophie Calle - L'Hotel, 1984

Photography's role in making and showing alternative realities has also been used in less specific but equally intriguing ways.

Melanie Manchot's series "Gestures of Demarcation" shows the artist expressionless and static asa second figure pulls the elastic skin of her neck.

This scene is not a performance being photographed but an act created for the express purpose of being photographed.

Melanie Manchot - Gestures of Demarcation VI, 2001

"Bread Man" is the performance persona of the Japanese artist Tatsumi Orimoto who hides his face under a sculptural mass of bread and then performs normal everyday activities.

The photographs representing these absurdist interventions are dependent on people's willingness and resistance to break with their daily activities in order to interact and be photographed.

Tatsumi Orimoto - Bread Man Son and Alzheimer Mama, 1996

The capacity of photo-conceptualism to dislodge the surface of everyday life through simple acts occurs in British artist Gillian Wearing's "Signs that say what you want them to say and not signs that say what someone else wants you to say".

For this work, Wearing approached strangers and the streets of London and asked them to write something about themselves on a piece of white card; she then photographed them holding their texts.

By making the thoughts of her subjects the focus of the portraits, Wearing proposes that the capturing of the profundity and experience of everyday life is not intrinsic to the traditional styles or compositions of the documentary photograph, but is more effectively reached through artistic intervention and strategy.

Gillian Wearing - Signs that say what you want them to say and not signs that say what someone else wants you to say, 1992

The enjoyment of such a photograph is based on our shift from registering a photographic image as a three-dimensional scene and that of a two-dimensional, graphic representation of the swirls of wet hair that we connect, via Van Gogh, to a patterned sky.

Mona Hatoum - Van Gogh's Back, 1995

The American photographer and poet Tim Davis's series "Retail" depicts the darkened windows of American suburban houses at night, with windows reflecting the neon signs from fast-food joints.

The photographs reveal a subliminal imposition of contemporary consumer culture onto domestic life.

With the repetition of this night time phenomenon express his theory of the contamination of our privacy and consciousness by commercialism.

Tim Davis - McDonalds 2, Blue Fence, 2001

Thursday, April 17, 2014

Exercise 8: Varying the pose

The Exercise 8, the last of Part 1, asks to take some time to flick through a number of magazines that feature pictures of people, and to note the variety of poses that are used.

In addition to the basic ones of sitting, leaning, standing, walking, squatting, and so on, there are variations in the way the limbs are positioned, the hands, twists and turns in the torso, and more.

I have to set up a portrait session, and plan for my subject to adopt in turn at least three different basic positions (sitting, standing, etc.).

Within these, suggest to my subject, different limb positions.

Later, I have to review the results and assess how effective or attractive the variations were.

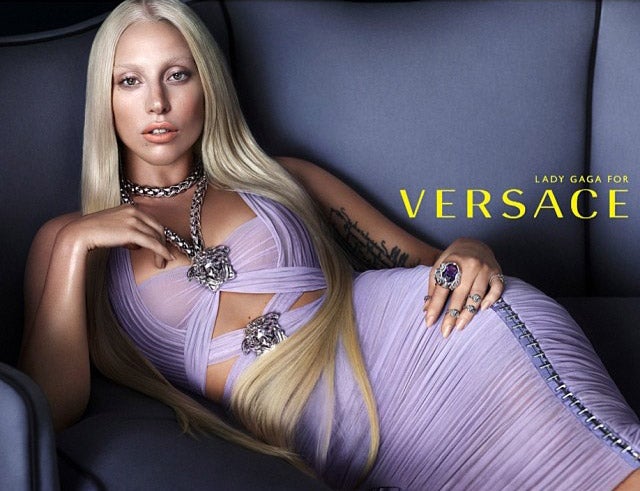

I decided to push a bit the limits of this brief and, I did not only take inspiration from the magazines, but I decided to reproduce three fashion advertisement photos.

Antonella is the most fashionable colleague I have and nobody else I know could have fit into this exercise better than her.

I believe she personifies the so called Italian style.

Almost a stereotype between perfection and exaggeration, action and seduction, intensity and joke.

When she spontaneously proposed to help me with my exercises, I immediately thought about this one for her.

I imagined that I could have very well leveraged her great aptitude towards the fashion business.

Antonella can be theatrical, with her soft, but almost arrogant look, with her thin body lost in the delicate folds of her dress.

Pure passion from South Italian roots, pure fashion attitude.

It was amazing and very interesting shooting a photo session with Antonella.

A true lesson of life.

Her world is diametrically opposite to mine, to my way of living life, to my way of taking photos and express myself by means of my camera.

However, I strongly perceived her love for fashionable details, clothes cuts, design, colours, make-up, accessories, as a true love, as a true passion.

And, at the end of the day, are not her pure love and passion the same than mines for photography?

Image 1.

In addition to the basic ones of sitting, leaning, standing, walking, squatting, and so on, there are variations in the way the limbs are positioned, the hands, twists and turns in the torso, and more.

I have to set up a portrait session, and plan for my subject to adopt in turn at least three different basic positions (sitting, standing, etc.).

Within these, suggest to my subject, different limb positions.

Later, I have to review the results and assess how effective or attractive the variations were.

I decided to push a bit the limits of this brief and, I did not only take inspiration from the magazines, but I decided to reproduce three fashion advertisement photos.

Antonella is the most fashionable colleague I have and nobody else I know could have fit into this exercise better than her.

I believe she personifies the so called Italian style.

Almost a stereotype between perfection and exaggeration, action and seduction, intensity and joke.

When she spontaneously proposed to help me with my exercises, I immediately thought about this one for her.

I imagined that I could have very well leveraged her great aptitude towards the fashion business.

Antonella can be theatrical, with her soft, but almost arrogant look, with her thin body lost in the delicate folds of her dress.

Pure passion from South Italian roots, pure fashion attitude.

It was amazing and very interesting shooting a photo session with Antonella.

A true lesson of life.

Her world is diametrically opposite to mine, to my way of living life, to my way of taking photos and express myself by means of my camera.

However, I strongly perceived her love for fashionable details, clothes cuts, design, colours, make-up, accessories, as a true love, as a true passion.

And, at the end of the day, are not her pure love and passion the same than mines for photography?

Image 1.

f 2.8, 1/4 sec, ISO 100, 55 mm

Image 2.

f 2.8, 1/4 sec, ISO 100, 55 mm

I started with a sitting position freely inspired by an add of Max Mara.

I prefer Image 1 for the intensity of the look (almost arrogant) and also because Antonella's posture seems to be more natural.

Obviously, I do not like very much the background of the two photos, but my PS skills are not good enough to perfectly replace the tiles with a uniform background.

Image 3.

f 5, 1/30 sec, ISO 100, 51 mm

Image 4.

f 5, 1/30 sec, ISO 100, 51 mm

Image 5.

f 2.8, 1/40 sec, ISO 160, 30 mm

Image 6.

f 2.8, 1/30 sec, ISO 200, 34 mm

In my view the shots in the leaning position are definitely better than the previous.

Antonella looks really at ease and in Image 4 the change of position well shows her theatrical attitude.

Once again, like in other exercises, I decided to get rid of my tripod and the result really pleases me.

I consider Image 5 and 6 interesting portraits with a nice narrative.

Particularly, Image 5 plays on the thoughtful look of the model in spacial relation with the shoes in the background: ephemeral and profound playing together.

Image 7.

f 5.6, 1/125 sec, ISO 100, 37 mm

Image 8.

f 5.6, 1/125 sec, ISO 100, 28 mm

Image 9.

f 5, 1/125 sec, ISO 100, 39 mm

I like both Image 8 and 9.

In the first one I appreciate the geometrical construction of the lines in the background associated with the shadows that the curves of the legs draw on the wall.

The second is very interesting for the luscious attitude shot by a photograph who appears just like a shadow in front of such a voluptuous woman.

Probably, the last three images would have needed a WB correction, but I really liked the soft, warm, natural light of an early spring sunset. Therefore, I decided not to correct the WB in post production.

Monday, April 7, 2014

Exercise 7: Focal length

In this rather basic exercise I am requested to plan to make exactly the same framing on a face of my subject with different focal lengths.

With a zoom lens, I have to use at least three: at either end of the zoom scale and in the middle.

Therefore, I needed to move the camera towards and away from your subject to keep the framing consistent.

Florence and I have been working together for the last 16 years and when, recently, I showed her this blog she generously and spontaneously offered me her help.

"I do not like to be photographed because I never look natural. Moreover, my son Quentin always pulls my leg when I show him photos of me".

Despite the relatively easy brief, given this statement, the shooting did not look as an easy task for me.

So, during lunch time, we decided to go to a park nearby and try to do our best: Florence with her alleged low ability to be photographed and I with my recent new role of portrait photographer.

Frankly, I think she was simply great!

Spontaneous, at ease, able to let herself guided by me: she was a perfect subject.

We spent about 60 minutes with a result of almost 200 shots at 10 different focal distances.

As usual, I showed the post production result to my subject and we decided to post the 8 best shots.

I am sure now Quentin will not be able to make fun of his mother photos any longer!

Image 1.

Image 2.

Image 3.

Image 4.

Image 5.

Image 6.

Image 7.

Image 8.

In my opinion, the above images are somehow self-explanatory.

Shorter focal lengths can distort facial features creating a caricature type portrait, hardly flattering.

An altered viewpoint can be used to generate a comical image, often seen in magazines and adverts.

Moreover, using a shorter focal length to capture a close up portrait, also involves physically getting closer and, unless you are really comfortable with your subject, this could be problematic.

In Image 2, 3 and even more in Image 1 all facial features are distorted.

The wider angle and my viewpoint has exaggerated my subjects nose out of all proportion, and causes the image to misrepresent the truth.

Florence's head seems too big.

Additionally, the shorter focal length draws the eye into the frame and the subject almost seems to be coming out towards the viewer.

These are not necessarily flattering portraits, but I find they have a certain charme and I think the wide angle effect can be rather interesting.

In Image 4, 5 and 6, there is less exaggeration of my subjects features. I feel her nose is still too prominent to create a truly flattering portrayal.

The focal lengths I used for Image 7 and 8 (respectively 150 mm and 210 mm), is not a focal length I usually use, but I think it fits perfectly to this exercise.

This focal length flatters the subject as all her features are less prominent and it creates a flatter composition.

These long focal lengths are useful when taking outdoor shots unobtrusively.

Using this lengths seems to have smoothed out Florence's skin.

I do like her facial expression and twinkling eyes.

Overall a good long focal length for a flattering portrait.

With a zoom lens, I have to use at least three: at either end of the zoom scale and in the middle.

Therefore, I needed to move the camera towards and away from your subject to keep the framing consistent.

Florence and I have been working together for the last 16 years and when, recently, I showed her this blog she generously and spontaneously offered me her help.

"I do not like to be photographed because I never look natural. Moreover, my son Quentin always pulls my leg when I show him photos of me".

Despite the relatively easy brief, given this statement, the shooting did not look as an easy task for me.

So, during lunch time, we decided to go to a park nearby and try to do our best: Florence with her alleged low ability to be photographed and I with my recent new role of portrait photographer.

Frankly, I think she was simply great!

Spontaneous, at ease, able to let herself guided by me: she was a perfect subject.

We spent about 60 minutes with a result of almost 200 shots at 10 different focal distances.

As usual, I showed the post production result to my subject and we decided to post the 8 best shots.

I am sure now Quentin will not be able to make fun of his mother photos any longer!

Image 1.

f 5.6, 1/180 sec, ISO 200, 18 mm

Image 2.

f 4.5, 1/180 sec, ISO 200, 24 mm

Image 3.

f 8, 1/125 sec, ISO 200, 35 mm

Image 4.

f 6.7, 1/180 sec, ISO 200, 45 mm

Image 5.

f 6.7, 1/180 sec, ISO 200, 55 mm

Image 6.

f 6.7, 1/180 sec, ISO 200, 70 mm

Image 7.

f 4.5, 1/350 sec, ISO 200, 150 mm

Image 8.

f 4.5, 1/250 sec, ISO 200, 210 mm

In my opinion, the above images are somehow self-explanatory.

Shorter focal lengths can distort facial features creating a caricature type portrait, hardly flattering.

An altered viewpoint can be used to generate a comical image, often seen in magazines and adverts.

Moreover, using a shorter focal length to capture a close up portrait, also involves physically getting closer and, unless you are really comfortable with your subject, this could be problematic.

In Image 2, 3 and even more in Image 1 all facial features are distorted.

The wider angle and my viewpoint has exaggerated my subjects nose out of all proportion, and causes the image to misrepresent the truth.

Florence's head seems too big.

Additionally, the shorter focal length draws the eye into the frame and the subject almost seems to be coming out towards the viewer.

These are not necessarily flattering portraits, but I find they have a certain charme and I think the wide angle effect can be rather interesting.

In Image 4, 5 and 6, there is less exaggeration of my subjects features. I feel her nose is still too prominent to create a truly flattering portrayal.

The focal lengths I used for Image 7 and 8 (respectively 150 mm and 210 mm), is not a focal length I usually use, but I think it fits perfectly to this exercise.

This focal length flatters the subject as all her features are less prominent and it creates a flatter composition.

These long focal lengths are useful when taking outdoor shots unobtrusively.

Using this lengths seems to have smoothed out Florence's skin.

I do like her facial expression and twinkling eyes.

Overall a good long focal length for a flattering portrait.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)